Relational Possibilities

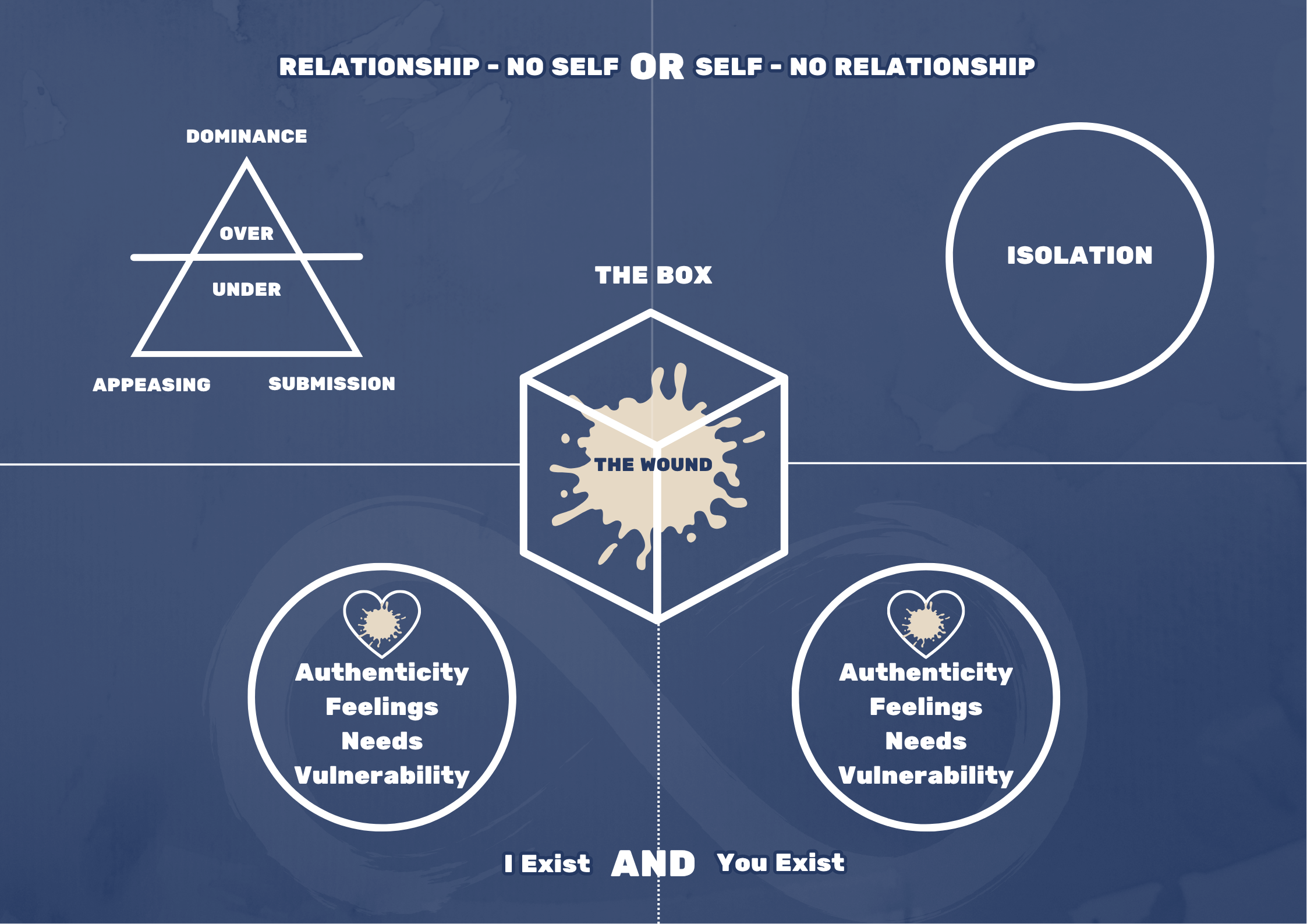

Figure: Adapted and reinterpreted from A Map of Relational Possibilities by Joanne Walker & Liz Coventry (2024), Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy.

The Map of Relational Possibilities: Understanding True Intimacy

A Way of Compassion Through Understanding

Relationships are where we experience our greatest joys, and our deepest wounds.

When things feel confusing, overwhelming, or stuck, it’s often because what’s happening between us isn’t just about the present moment, but about how our nervous systems learned to manage closeness and safety long ago.

The Map of Relational Possibilities offers a profound way to understand this journey: from early attachment to wounding, to the protective patterns that form in adulthood, and finally, to the possibility of healing through conscious relationship.

Let’s unpack it together.

We Begin in Connection

As infants, we are pure sensation, completely dependent, unfiltered, and open.

We reach out instinctively for safety, comfort, and joy. When a caregiver soothes us, we learn that the world is safe and that connection feels good. This is what Walker & Coventry call our healthy reach.

We also naturally pull away when something feels too intense or unfamiliar. This healthy push allows us to explore the world, self-soothe, and return when ready.

When both the reach and push are safe, we develop a flexible, secure sense of self-in-relationship, able to love and to be alone.

The Wound: When Safety and Connection Collide

But no caregiver is perfect.

Sometimes they become overwhelmed, distant, or collapsed—unable to meet our emotional needs. For a child, this feels terrifying: the very person who is meant to soothe becomes the source of fear or confusion.

Because we cannot escape or regulate ourselves yet, our nervous system learns one painful truth:

To stay safe, I must protect the relationship, even if it means losing parts of myself.

This is where the wound begins.

The Box: Protecting the Wound

To survive, we put our overwhelming feelings, shame, terror, rage, need, into a “box.”

We learn which parts of ourselves are acceptable and which must stay hidden.

This helps maintain stability in our family, but it comes at a cost: authenticity.

We start shaping ourselves around others’ needs to prevent disconnection.

This is not weakness, it’s intelligent adaptation. But if left unhealed, it becomes a relational pattern that repeats in adulthood.

The Triangle: Surviving Through Roles

Walker’s triangle describes three adaptive roles we take on to maintain safety in relationship:

Appeasement: “If I please you, I’ll be safe.”

Submission: “If I make myself small, you won’t get upset.”

Dominance: “If I stay in control, I won’t be hurt again.”

We move between these roles, constantly scanning for how to keep peace or avoid rejection. It works temporarily, but keeps love conditional. Relationships become about managing tension, not connection.

This is what we call enmeshment, where self and other blur, and “power-with” (mutual respect and autonomy) is replaced by “power-over” or “power-under.”

The Self in Isolation

Eventually, we may rebel against this.

We withdraw to reclaim autonomy, building thick emotional walls to feel safe again.

Here, we rediscover our “self,” but at the cost of intimacy.

In this space, we might think:

“I can take care of myself, but I’m lonely.”

“I’ll never let anyone control me again.”

It’s the other side of the same coin, self without relationship.

The Dilemma: Self or Relationship

When couples come to therapy, they are often oscillating between these poles:

Enmeshment (self-loss)

Isolation (connection-loss)

Neither feels sustainable. We long to be known without disappearing and to be free without losing love.

The solution lies not in choosing one, but in evolving toward something new.

The Path Forward: Differentiated Selves-in-Relationship

Healing begins when two people each commit to being fully themselves while staying in connection.

This means:

“I am me, even when you’re upset.”

“You are you, even when I’m scared.”

“We impact each other, but neither controls the other.”

This is differentiation, the capacity to remain grounded in self while being emotionally connected.

It’s where true intimacy begins: where both power and vulnerability coexist.

Letting the Wound Out of the Box

When we move toward differentiation, our old protective patterns shake loose.

The wound we boxed away surfaces, grief, fear, shame, and it can feel like everything’s falling apart.

This is often when couples say, “It’s getting worse!” But in truth, it’s healing.

What’s been hidden is finally asking to be seen.

In therapy, we slow this process down, helping each partner meet the re-emerging feelings with compassion rather than re-enactment.

Reclaiming the Wound with Love

The final movement is integration.

We learn to hold our wounded parts, not with judgment, but with tenderness.

Instead of trying to fix or exile them, we listen:

“What did I need then that I can offer myself now?”

When both partners begin to relate to their own wounds this way, the relationship becomes a container for mutual growth, not a battleground for unmet needs.

This is power-with, the foundation of conscious love.

Reflection Questions for Couples

What are some common situations I feel triggered in my relationship?

When I am triggered, do I tend to appease, submit, dominate, or take control?

When I am triggered, where do I feel it in my body, what does it feel like?

What is something I can do to love myself in these moment while still being loving to those around me?

Closing

Healthy relationships are not about avoiding wounds but integrating them.

When we bring awareness, compassion, and courage to our patterns, we discover that our deepest pain points are the gateways to genuine intimacy.

True connection doesn’t mean losing yourself, it means finding yourself with another.

Acknowledgement

This post draws inspiration from A Map of Relational Possibilities: Translating Theory into Practice by Joanne Walker and Dr. Liz Coventry, first published in the Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy (2024) (DOI: 10.1002/anzf.1609)

Their paper outlines a novel model for understanding how relational trauma shapes human connection and how healing unfolds through differentiation and love. What follows is a translation of their brilliant framework into language that couples in therapy can use to better understand themselves and each other.